The Spalpeen

Oughterard Newsletter September 2012

By Michael O'Connor

Emigration seems to be part and parcel of our history here in Ireland. There has never been a period when it disappeared completely. A sad reflection of international events and circumstances maybe, it is always evident because a certain section of the people chose to emigrate, to travel abroad to explore foreign lands and see for themselves the faraway places, they had so often read about. But there was another, far different reason to go. It was out of pure necessity for many others. Having no job, no means of support, weighed down with bills, often incurred while rearing a family. An expensive time in household, so many people chose to emigrate.

Many of those who left in the early 30s and 40s never returned. World War II began in 1939 and it became risky to travel for many years. So anybody who went to England stayed until the War was over. Many of the men folk joined the army as other jobs there were scarce. However many Irish men went to Scotland and helped to harvest the potatoes. The Scotsmen had to go to war too. Years later Irish lads went to the English midlands to harvest the beet crop. This turned out to be an annual event for many years.

Here at home around that time, many young lads decided to make themselves available for seasonal farm work. Many of them were from the west Galway area and they were native Irish speakers.

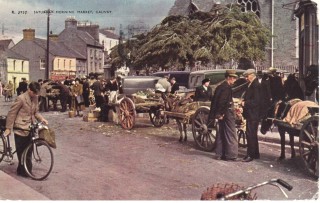

They decided to assemble at the Galway Saturday Market. They dressed in beautiful Connemara Tweed suits and many wore caps. Caps had been worn by Irish lads right through the 1930s. So these lads presented a pretty picture in Galway Market every Saturday. The wealthy farmers from East Galway needed help to sow and harvest their crops. They had heard about these lads who were all of farming stock and they approached them and within a short time an arrangement was arrived at and all the lads were hired. These lads were known as spalpeens. They usually worked in pairs on each farm.

After meeting these lads the hirer took them to his home in East Galway and from that moment they were treated as members of his own family. They had their own bedroom and each day after work they all had meals with the hirer’s family. So they were treated as family members. They mixed well with the locals and many of them were storytellers, singers, sean nós dancers and musicians – they were invited to all the local ceilís and parties, they made many friends too. They would all return to their own homes in time for Christmas. These spalpeens didn’t want to emigrate – they enjoyed this very varied work they had just started and they were only beginning.

This was the start of a very successful exercise. The spalpeens would help to plough the soil and plant the crops. When that was done, it was time to start cutting the turf. The turf was cut with a slean and spread in a wheelbarrow. This took a few weeks and then it was time to “turn the turf”. A few weeks more and the dried turf was fit to be taken home. This was done with the aid of a horse and cart or donkey and cart.

The spalpeens were still there, ready for their next assignment and that was reaping the harvest. This was done by reaping hook, a slow process. The corn was then stacked in stooks and left to dry out for a few days. Then it was taken home and made into a stack and left there until threshing day later on.

Now this was the last big job of the season. It was at this point that the hirer decided he would let these gallant spalpeens home after having completed a very successful season in his service.

Along with being expert farmers these lads were Irish speakers, which they spoke daily. Many of the locals picked up the Irish phrases and within a short time Irish was being spoken in most of the area. This was a wonderful development and today, many years later, these areas are now mini-gaeltachts. What a wonderful legacy left behind by the spalpeen, a treasure for future generations.

In fact the spalpeens were needed for a further twenty years, right up to the early ‘60s, when the farmers began to get acquainted with modern machinery for the very first time. Then and only then did the whole concept of farming change, never to be the same again. For now gone were the old ways of getting things done manually. And a modern era had dawned. The days of the spalpeen were numbered.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page