Oughterard Poor Law Union

By Culture and Heritage Group

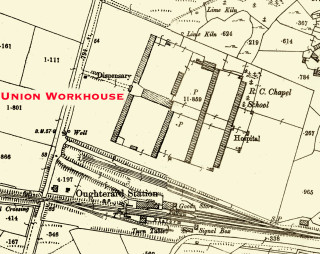

Oughterard Poor Law Union was one of the second wave of Irish unions created between 1848 and 1850. Oughterard Union formally came into existence on 8th October 1849. It was formed from the western part of the Galway alway Union and occupied an area of 271 square miles. The population falling within the Oughterard Union at the 1901 census had been 17,732. In 1905, it comprised the following electoral divisions:

Co. Galway: Camus, Cloonbur, Cong, Crumpaun, Cur, Gorumna, Kilcummin, Letterbrickaun, Letterfore, Lettermore, Oughterard, Ross, Turlough, Wormhole.

The Guardians met at the workhouse on Tuesdays

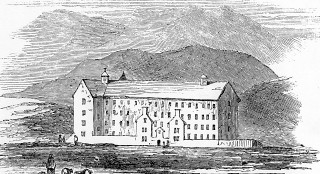

The building cost £5,950

The new Oughterard workhouse, for 600 inmates, occupied an eight acre site at the south-west of the town. The building cost £5,950 to construct, plus a further £1,055 for fixtures and fittings. Designed by the Poor Law Commissioners’ architect George Wilkinson, the building followed a design similar to that used for other workhouses erected during this period, for example at Claremorris or Tubbercurry. At the west, facing the road, a central entrance gate was flanked by two long blocks, usually allocated to children’s accommodation and schoolrooms. To the rear, a T-shaped main building contained kitchens, dining-room and chapel at the centre, with accommodation blocks for adult male and females to each side. At the rear was a separate hospital block.

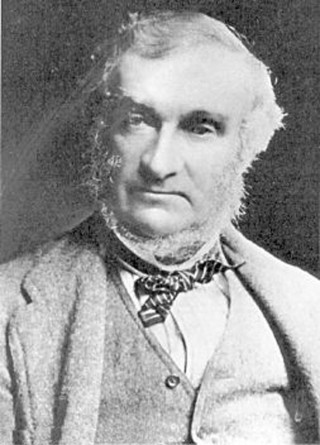

Workhouse architect

George Wilkinson was born in Witney in Oxfordshire, the son of a carpenter and builder. His first workhouse commission was in his home town of Witney where Sampson Kempthorne had been invited to supply plans. However, Kempthorne upset the Witney Guardians several times, most notably in proposing a brick-built design for a town which was built almost entirely in local Cotswold stone. Wilkinson was given the architecural contract but failed to secure the building contract for his family firm.

Workhouse residents

Upon arrival at a workhouse, the head of a pauper family would be harshly questioned to prove his family had no other way of surviving. Once admitted, families were immediately split up, had their old clothes removed, were washed down, then given workhouse uniforms. Men and women, boys and girls had their own living quarters and were permanently segregated. Workhouse residents were forbidden to leave the building. The ten-hour workday involved breaking of stones for men and knitting for the women. Little children were drilled in their daily school lessons while older children received factory-style industrial training. A bell tolled throughout the day signaling the start or end of various activities. Strict rules included no use of bad language, no disobedience, no laziness, no talking during mealtime and prohibited any family reunions, except during Sunday church.

Three-quarters empty

The 130 pre-famine workhouses throughout Ireland could hold a total of about 100,000 persons. Everyone knew that entering a workhouse meant the complete loss of dignity and freedom, thus poor people avoided them. Before the Famine, workhouses generally remained three-quarters empty despite the fact there were an estimated 2.4 million Irish living in a state of poverty.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page