Introduction

SSE-Airtricity developed a wind farm in County Galway consisting of 22 wind turbines and associated infrastructure in two townlands; Uggool and Lettercraffroe. RoadBridge – Civil Engineering and Building Contractors undertook the civil construction of the windfarm. Archaeological monitoring by Archaeological Management Solutions, of groundworks associated with the construction works revealed two previously unrecorded cereal drying kilns. These kilns appeared to have been placed in locations that were hidden from view. Further enquiry revealed that they were deliberately hidden. The kilns provide a tantalising glance at the secrecy associated with the production of poteen, an illegal activity prevalent in this and other rural areas of Ireland from the eighteenth century.

The kilns are located in the townland of Uggool, which is located approximately 5km to the south of Oughterard, Co. Galway. Uggool townland is situated along the side of a hill and consists mainly of hilly peat and natural rock outcrops. Natural boulders are located throughout the townland, with an abundance of the boulders deposited along the central river valley. Three RMP sites are located within the townland. These consist of a standing stone (GA067-028), cairn (GA067-025) and sheepfold (GA067-023).1 These sites will not be impacted by the works associated with the Wind Farm construction. There is one occupied dwelling in Uggool where brothers Tom and Padraig Walsh live. There are also the remains of approximately ten drystone walled houses in the townland, probably dating to the nineteenth century. These houses were isolated from the nearby villages. Up to twenty years ago, there was no access road into the Walsh house. The current road was constructed to provide access for forest operations. The residents of this area would have trekked over Uggool Mountain and walked the 5km into Oughterard.

1 Environmental Impact Statement for the Redesign of Feirm Ghaoithe Oguil, near Oughterard, Co. Galway. December 2011, Fehily Timoney & Company, p.238.

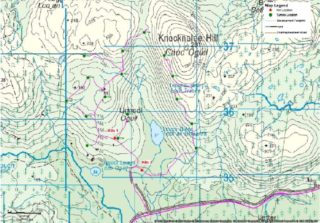

Figure 1. Map showing location of the Windfarm. Locations of Kilns 1 & 2 are highlighted.

Figure 2. Aerial view, showing locations of Kilns 1 & 2.

The Kilns

Up to the mid-1800s, cereal-drying kilns were found in almost every townland in Ireland. In this country, they were mainly used to dry grain and to harden it prior to grinding for use in bread-making. The basic kiln was made up of four main structural parts; a bowl, a flue, a stoke-hole and a drying platform. Kilns were frequently built into banks or slopes when a large part of the structure was hidden below ground level. However in hilly areas like Uggool, built-up kilns were constructed, often in areas to make full use of the prevailing wind and used on days ‘when the wind direction assisted the convection of air through the flue to the drying platform’. 2 It was probably also the case that due to the frequent inclement weather in this part of Ireland, the kilns at Uggool had roofs made of wood, sod or straw.

2 M. O’Sullivan and L. Downey 2005 Corn-drying kilns. Archaeology Ireland 19(3), p.33.

Kiln 1 is situated halfway up a hill, located in an area with an abundance of natural boulders. This kiln is bordered to the south by a very large natural boulder. The kiln is roughly oval in shape, with dry stone walls surviving to a depth of on average 1m. The width of the kiln bowl wall is between 0.6-0.7m and it measures 2.8m in diameter. The stone flue (1.1m in length and 0.5m in depth) is located at the west of the kiln. This kiln is not visible in the landscape until close to it and its location and setting was purposely hidden.

Plate 1. Kiln 1, looking south. Note how the kiln is built to incorporate the large boulder, which also hides it.

Plate 2. Kiln 1, looking north.

Kiln 2 was built into a stone field wall. The oval stones that formed part of the kiln wall were not in keeping with the rest of the larger stones in the field wall. Upon further investigation, the curve at the base of the wall tuned out to be the base of the kiln bowl. Only the southern wall of the kiln, the part built into the stone wall survives. This wall measures 1.3m in height and 1.2m in width; on average 4-5 stones wide. The remainder of the bowl consists of only a stone

in depth. The sub oval bowl measures 0.65 x 1.2m. The remainder of the kiln was dismantled at some stage, after it went out of use. Cut stone that may have formed part of the original kiln were later reused in the repair of the field wall.

Plate 3. Kiln 2, built into field wall, looking northeast.

Plate 4. Kiln 2, looking south.

There was a concerted effort on behalf of the builders of these kilns to ensure that the kilns were hidden from view and not immediately obvious in the landscape. The reason for this became clear after discussions with locals. This area was well known in the last two hundred years for poteen production. It was important to hide the sites and tools involved for the various stages of its production from view. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,

officers from the R.I.C and later An Garda Síochána from nearby Moycullen would regularly walk out to the townland and destroy any sites or paraphernalia associated with poteen production.3 A counter-measure adopted here in Uggool, as elsewhere to prevent detection, was to carry out the different stages of poteen production in different areas.

3 Interview with Padraig and Tom Walsh, 11/08/2015.

4 Déantús an Phoitín DVD, 2010. Publisher: Léirithe le Mac Dara Ó Curraidhín

5 Interview with Padraig and Tom Walsh, 11/08/2015.

6 Interview with Padraig and Tom Walsh, 11/08/2015.

7 Liam Mac Con Iomaire, Ireland of the Proverb. Ireland. 1998. p.134

Poteen Production

On Christmas Day in 1661, the British Government introduced a taxation on all alcohol; that was later introduced to Ireland. In 1760, private distillation was outlawed and a licence to distil had to be obtained. This was to make it easier for taxes on alcohol to be collected.4 With these new laws and a crackdown on illegal stills, production of poteen was restricted to more rural areas.

Traditionally, there were a number of stages involved in the process. Firstly, the grains used in Uggool were barley, oats and rye; these were wrapped and submerged in water. They were then drained and spread out in a shed or dry area to germinate. This was known as the malting process, when the starch converts to sugar; which in turn was later converted to alcohol. The amount of time the grains were left to malt was considered vital to ensure best quality. In Uggool, the poteen makers considered three weeks to be the optimum time, with the grains evenly turned each evening.5

Next the grains were hardened in the kilns. Traditionally it is thought that this stage of poteen production was updated in the later twentieth century and kilns were no longer used. But here in Uggool, on the border of Connemara, oral history suggests that kilns remained the preferred method of drying the grains into the early twentieth century.6 The hardened, swollen, sweet grains were ground and placed in a wooden barrel, where almost boiling water was poured over them. Baker’s yeast was applied to cause fermentation. After about three days, the brew was transferred to the still. The heat under the still caused the alcohol vapours to rise and these passed through what is commonly referred to as the worm; a coil of copper piping placed in cold water. The alcohol vapours condensed and the liquid, known as a singling was collected and sent through the still again (doubled) to create poteen.7

During construction works at Uggool, an interesting piece of apparatus was located to the side of a large boulder, approximately 400m east of Kiln 2. Upon closer inspection, it seems that this is the remains of a copper worm. The worm measured approximately 1m in length and consisted of a piece of copper twisted in a circular shape and held in place by string and wood. It was misshapen and had been discarded at some time in the past when it no longer served its purpose. The state of this worm indicates that it is probably over a hundred years old.

Plate 5. Poteen worm discovered during construction works.

War on Poteen

The R.I.C. Magazine in 1912 reported that in nearby Carraroe, which like Uggool is in the district of Ougherard, revenue seizures suggested that illicit distillation was still prevalent in Connemara. ‘These figures it may be mentioned, show a decrease over those of the previous years:- Number of seizures, 85 ; number of prosecutions, 19 ; amount of mitigated fines imposed £122 ; number of stills seized, 27 ; number of worms seized, 7 ; gallons of wash seized, 4,768 ; gallons of illicit spirits seized, 82. Total value of seizures, £ 251 – 17s – 8d.’8

8 R.I.C. Magazine, February 1912. Galway. W.R. Force Notes.

From the 1920s, the social problems associated with poteen consumption was fought on two fronts; An Garda Síochána and the Redemptorists Fathers, part of the Temperance Movement. The Redemptorists set about travelling the

county, encouraging locals to attend their missionaries, take the anti-poteen pledge and surrender any poteen-making equipment and spirits. The evils of those taking poteen were recorded in each parish. Their sins included dancing, mass-missing and neglect of the sacraments. The mission reached Ougherard in July-August 1934 where it was reported that shebeens (illicit drinking areas) were spotted in some outlying areas, but all participants took the pledge. Nearby Collinamuck posed a greater challenge and was reported thus ‘A stubborn and ignorant people debauched by poteen. They told barefaced lies and only with great difficulty did they surrender four stills. All but four took the anti-poteen pledge, but their earnestness is doubtful.’9

9 Brenden McConvery, ‘Hell-fire & Poitín Redemptorist Missions in the Irish Free State (1922-1936)’ in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 2000), Volume 8.

There is no record of the missions reaching the townland of Uggool or no evidence that anyone in the townland was prosecuted for poteen manufacture. The kilns uncovered during the Wind Farm construction probably date to between a hundred and a hundred and fifty years old. They offer us a hint of the secrecy that surrounded the practice. The importance of each stage and careful consideration of the types of materials and tools used to create a high quality product have survived in oral history. A cursory look at areas outside of the scope of the current project would suggest that the two kilns found are among many hidden behind boulders and field walls in this landscape.

Acknowledgements

The residents of Uggool, Padraig and Tom Walsh have been very generous in their sharing of the history, stories and knowledge of the area. Ed Danaher (AMS) gave invaluable and constructive comments on the first draft. Kim O’Meara (Roadbridge) created the figures. I wish to acknowledge SSE and Roadbridge for their support in the writing of this article.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page