The Great Potato Famine 1845-1848

By Mary Kyne

The 150th anniversary of the start of the “Great Potato Famine’ was commemorated in 1995. I wrote a number of articles in 1995 on the effects the famine had on the Oughterard area during that period. I published the articles in the Oughterard Newsletter. My principal reference books were:

Souperism Myth and RealityThe Protestant Crusade in Ireland 1800- 70” by Desmond Bowen

Connemara after the Famine by Thomas Colville Scott

Cry The Cursed Land ( Ireland’s Holocaust) By Louie Byrne

T he Workhouses of Ireland by John O Connor

The Great Hunger by Cecil Woodham-Smith

Surveys, I am told, indicate that Irish people do not want to hear about the Famine. It doesn’t surprise me in the least. But this is also precisely why the subject must be talked about until we remember the things we never knew. All nations who have suffered trauma similar to our own have come, sooner or later, to the realization that they must return to the past one last time in truth and reverence before they can make the first real steps into the future. We should not remember out of a thirst for retribution or recrimination but out of a need for serenity and knowledge.

General Facts

The real disaster of the Famine was the longevity of the Famine. Few people suffered acutely from the Famine between 1845-1846. The Famine would not have got star billing in the history books if it had only lasted for that year. The huge numbers of deaths occurred during the winter of 1847/1848 and 1848/1849, and then things didn’t get back to normal until 1850. During the Famine at least one million people died, mostly from diseases such as cholera, while vast numbers emigrated.

Half the food in Ireland was lost

To help us understand the ‘holocaust’ of the Famine we must also realise that famines, in other countries, have been caused by a 10% loss of food, but between 1846 and 1847 half the food in Ireland was lost. The extent of food scarcity was higher than some modern Indian and African famines.

Many will also argue that food should not have been exported from the country at this time but to stop the exportation of food produced in the country would have required the assumption of powers that no contemporary government possessed, and would have caused violent resistance among the farming classes. In any case from 1847 Ireland was importing five times as much grain as she was exporting.

A Writer’s View of Oughterard 1843

1843 William Makepeace Thackeray traveled through Oughterard on his way to Clifden. He commented on the contrast between “the healthy looking people in huge servant households of the gentry and the cowed, country people, shy, sly and silent”. He also noted the large and handsome poor houses that had been constructed. Thackeray also noted the various characteristics of the west of Ireland peasantry.

West of Ireland Peasantry

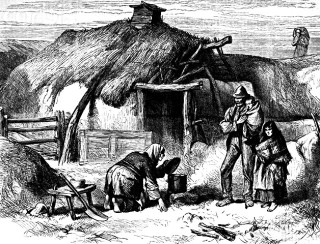

Many peasants held their land under the evil conacre system which gave them the right to occupy the land but not the right of conveyance by will or lease. In this area they rented from a rood to two roods of land, which “neither their capital, nor their acquaintance with agricultural science enabled them to render productive.” The potatoes, which they planted and on which they relied upon for their subsistence, were seldom in sufficient quantity to last during the entire year. An extra burden was also placed on them when they were compelled to devote their principal crops to the payment of their rents.

Died in their hundreds of thousands

Travellers to the area were also surprised that the people would not consider any method of cooking except ‘boiling”, or any diet except the ‘potato’. This ignorance complicated the work of relief agencies during the Famine. Many people didn’t know how to cook Indian corn when it was distributed to them and died of dysentery as a result. When famine upon them they were either so near the margin of human existence, or so frightened and despairing that they lay down quietly and died in their hundreds of thousands. People in almost every village and every town land in this area will tell you of unmarked famine graves. The vast majority lived in one-room cabins. They remained illiterate Irish speakers. They were poverty stricken, socially depressed members of a rural culture that was different in many ways from the sophisticated world beyond the Shannon.

Implication For Religion

For many of the peasants in the area the Famine years were a time of religious crisis, and their agony was spiritual as well as physical. As far as the peasant was concerned two ecclesiastical establishments, the Catholic Church and the Protestant Church, preyed upon him and sometimes the priest was tougher in his extraction of his “dues” than the parson was in demanding “tithes”. Both churches depended ion these subscriptions for their upkeep. Archbishop Oliver Kelly gave evidence that “ The people of the far west and South-east of Ireland had long been neglected by the Roman Catholic authorities”. It is also significant that at this time the spirit connected with unscrupulous proselytizers and distributors of relief originated in these areas – a deep and abiding gloom descended upon the peasants and when scripture readers spoke of the Famine as a “divine visitation for national sin”, many listened, and responded in a way that was unusual for them. The Irish Protestant Missionaries put a melancholy emphasis on this earth being no place of abiding joy, and God being a remote and terrible judge of mankind. The theology suited the mood of depression which descended upon the people and it is probable that some of the success of the proselytizer in the area; the Rev. Alexander Dallas came from preaching a message which suited the spirit of the time.

Where did the ‘Potato Blight’ originate?

In June 1845 reports began to come from Europe that a new blight had been noticed in Belgium. It is not known for certain where it came from but it had been in America from 1843 and may have been imported with guano (fertiliser) from South America. It spread into France, Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands and England, and caused huge crop failures in which thousands of people died. In these countries people were less dependent on potato as a food, unlike the Irish. A severe drought in Europe in 1846 helped to kill the blight completely.

Scientists’ Viewpoint

At first scientist could not agree what caused the potatoes to rot and turn black. They blamed the cold weather, or insects, or some poisonous “miasma” in the air. However, it was later found to be a fungus with its spores carried on the wind. If the spores were buried in the pits where the potato crop was stored, they would spread again when the new seed potatoes were planted in the spring. It was 40 years before a spray was developed to fight blight. In the first year of the blight no one could imagine that it would last for so long, decimating the population and draining a reluctant Britain of enormous sums of money.

Attitude of the British Government

The attitude the British adopted was that everyone was supposed to be self-sufficient and that to give charity was to weaken the peoples’ ability to look after each other.

The people of this area were not able to look after themselves. 10,900 people were fed in Oughterard in 1847 in one day alone. The population of the area at the time was listed as 10,601 (British Parliamentary papers, Shannon Series Famine 8). Obviously a lot of pressure was put upon the local poorhouse at this time as people moved in from Ballinrobe as Ballinrobe Workhouse was closed in July 1847.

Concern of the Clergy

The priests of Oughterard – Fr. Castiaux and Fr Geraghty were concerned about the plight of their parishioners who had by now come under the influence of Alexander Dallas and John O Callaghan, two extreme proselytizers in the area. They wrote long letters to the ‘Galway Mercury” stating their case and begged the people of outlining areas for financial assistance to feed and cloth their flock. They implored their fellow priests to come to help them convert their people back to Catholicism again. Their fellow priests did not fail them. The Vicar General, Rev. B. S. Roche and Fr Godfrey Mitchell came to Oughterard June 23rd 1850. They preached to the people making references in their sermons to the Old and New Testament, proving to their congregation that they too had a knowledge of the Bible.

With Tears in their eyes

In 1851, Rev Fr. Marshall and Fr. Montgomery arrived in November. They were both converts to the Catholic religion and as a result of their sermons a large number of people returned to the Catholic faith, ” with tears in their eyes”. The morning after their sermons there were only nine children present in the Mission school out of a total of 110. The same thing happened in Rosscahill. The tide was turning

Rev. Fr. Michael Kavanagh Appointed P.P. to Oughterard 1852.

January 1852 Fr. Kavanagh, a native of Galway was appointed Parish Priest of Oughterard. Fr Castiaux was transferred to the parish of St. Nicholas East.

Fr. Kavanagh tells us that when he first received news of his appointment he was over whelmed by the magnitude of the task facing him. In addition to the difficulties arising from the famine he had also to contend with “souperism’ which was taking advantage of the physical distress of the people.

Shortly after his arrival in Oughterard he became a member of the local organization for the ‘Rights of Tenants”. Early in March, on behalf of the tenants, he addressed a meeting on the “Ecclesiastical Titles Bill” in which he condemned the bill as an insult to the Irish Nation and to the Catholics of the Empire.

New Schools

1852 Christopher St. George – a landlord in the area who resided at Tyrone House, Kilcolgan gave Fr. Kavanagh sites for the erection of schools at Leam and at “Gort an Seangán”, Glann.

Robert Martin gave him a site at Collinamuck.

At that time in Leam about one hundred children were being educated in a leaky cabin on the mountainside, which, in turn had replaced a hedge school of Penal times. Some children attended school at nearby “ Glengowla”, now known as “ Glengowla Lodge”. Glengowla school was run by the Irish Church Mission and the school master, on a salary of £20a year, was obliged to teach scripture according to the Authorised Version of the Bible for no less than two hours a day. When the new Leam School was opened 1877, all the pupils deserted Glengowla and the building reverted to the O fflahertie landlord. The one-roomed school built at Leam by Fr. Mc Donagh (who replaced Fr. Kavanagh), was replaced by the present Derryglen School built 1959.

The old school in Collinamuck was replaced in 1950 by Rev. Canon Mc Cullagh . The Canon later opened the Boys’ school – St Cuimin’s Oughterard 1971.

Comments about this page

Looking for info on the von schwictenberg family in Germany

Add a comment about this page