The Irish Race

Bill Daly

Scattered over the surface of every country in Europe may be found ancient monuments, the remains of prehistoric times and nations, and of a phase of life and civilization which has long since passed away. The peoples by whom these works were made, so interesting in themselves, and so different from anything of the kind erected since, were not strangers and aliens, but our own ancestors, and out of their prehistoric civilisation our own has slowly grown. No record or tradition has been bequeathed to us, or of its nature, ideas or sentiment, how it was sustained, only by excavation and extrapolation can we learn anything.

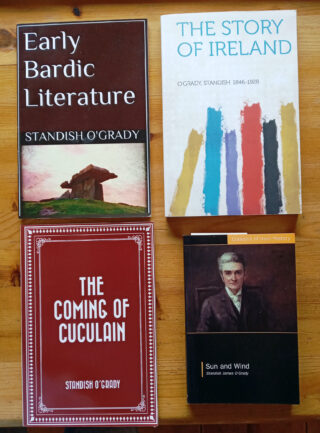

The following are some words from Historian & Folklorist Standish O’ Grady (1846-1928). He is rarely mentioned these days, and this excerpt is from his book ‘The Story of Ireland’, published in 1894.

‘In ancient times the country was full of bards, who, with their harps, used to travel from one house to another, singing songs for the people about the island in which they lived, and the brave deeds of their ancestors. These bards had three names for Ireland which they used more often than others. They called it Banba when they thought of its plains, woods, and mountains; and Fodhla when they thought of it in connection with learning, laws and history; and Eire when they thought of its warriors , heroes, and kings. The bards, too, used to celebrate the valour and excellence of an ancient hero called Ir, and so got into the habit of alluding to the island in their songs as the land of Ir. So we get the name Irland or Ireland , which is in everybody’s mouth today, though it was first invented over two thousand years ago by one of those makers and singers of songs who used to go about the island with their harps, amusing the people and also instructing them in their history. No one knows that bard’s name, or anything about him, yet the word that he invented is known all around the world today’

I first came across the name Standish O’Grady while I was attending Lismore CBS in the early 1970’s. At the beginning of second year we got a new teacher called Brother Collins and now and again he would say to us –‘If you ever come across any books by Standish O’Grady, let me know’. We never did at the time, but over forty years later when I came across them, the words from Brother Collins were ringing in my years. Strange how things happen at time, and I believe now that there are very few coincidences in this life. I have expanded my book collections from O’Grady in subsequent years, and I would particularly recommend him to anybody who has an interest in prehistory, history and folklore. O’Grady makes an interesting point that the vast majority of our megalithic monuments are referenced in the ancient texts and we would be unique within Europe in this context. Based on this we can match the stories and legends with the people who were associated with and possibly built the monuments. We were always a nation of storytellers, devoted to the tales of long ago, the memory of our ancestors, and many of the tales have been enhanced and embellished over time.

Many of the great manuscripts that have passed down to us today were written by Monastics between the 8th and 10th centuries of historical time, and for the most part the subject matter deals almost exclusively with the lives of the Saints. This made sense in the early days of Christianity as the new religion was being rolled out and promoted across diverse geographical zones. However, there is one major exception to this early literary output, and that is ‘Leabhar Gabhál na hEireann’ or more commonly called ‘The Book of Invasions’. The Leabhar Gabhál is different in that it purports to detail the tribes that invaded Ireland in succession from the beginning of time. In all there are six major invasions outlined in the following order: Cessair, Parthalon, Nemed, Fir Bolg, Tuatha De Danann and Milesian. Of particular interest to us are the Tuatha De Danann who can be roughly equated with a golden period for Ireland during the Bronze Age and much of the ancient legends and stories handed down to us today emanated from this period.

It is speculated that the Bronze Age (2500 – 500 BC) people came from the area we now call Central Europe, and they brought to these shores a technical knowledge of mining, smelting and metalworking. For Ireland to have a Bronze Age we needed to have ample deposits of copper, gold and tin. We were rich in copper and gold and we had to import the tin from Cornwall or Spain. The main areas of copper mining during this period would have been the coastal areas of Waterford, Cork and Kerry. The early tools and implements were made from copper, and then they discovered that if they added 20% tin to 80% copper they would get a tool that was harder and more durable. This alloy was called bronze. We have ample evidence of the Bronze Age in and around Oughterard and I hope to be in a position to present the evidence for this during Heritage Week 2022 in a face-to-face setting. The following features would have been specific to it – copper palstave axes, cairns, cist burials, fulachta fiadh, crannogs, stone circles and standing stones. It was the beginnings of our modern society, and quite possibly the origin of our folklore, Brehon Laws and the Irish language.

Standish O’Grady, along with Yeats, Lady Gregory, John Millington Synge and George Russell (AE) were part of the ‘Celtic Revival’ movement in the late 19th and early 20th century in Ireland. Jack B Yeats (brother of W.B.) progressed this vision also through his wonderful paintings which reinforced the rugged Connemara landscape and the natural people who lived out their lives upon it. In the aftermath of the Famine, due to the huge number of deaths, emigration and the continuing decline of the Irish language, they sought to rescue and preserve the ancient legends and bring them to a modern audience in the English language. William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) was forefront in this movement and a dedicated exponent of Irish folklore who took a particular interest in the tales mythic and magical roots. There was a bit of a backlash at the start by using the English language as the medium to do this and Olivia O’ Leary has an interesting insight on this from the documentary ‘A Fanatic Heart – Geldof on Yeats’…

‘I think the wonderful thing for me was that he gave us the beginning of a literature that was identifiably Irish but in the English language. I think what Yeats did for me was that he gave us a way of being Irish but in the English language which was my mother tongue, the language I grew up speaking (it was the tongue of modernity). It did not exclude me from Irishness because my Irish wasn’t fluent, and the fact of the winning of the Nobel Prize showed that there was a world recognition of this poet and the literature that he championed. We didn’t have to feel ashamed of it, or feel it was second rate or anything – this had been recognised internationally and we could embrace it without feeling that it was the colonist’s language’.

A comment was made some years back that the only apparent outward semblance of Ireland achieving freedom from Britain was the fact that the post-boxes were painted green instead of red. This should be taken in the humorous context in which it was meant to be delivered. In 1921 we did not have an awful lot to start with but we were fortunate to inherit the British Civil Service. Some time ago I noticed two wall mounted post-boxes in Cork bearing the royal insignia underneath the green paint. The original British Post Office boxes were bright red. When Ireland gained Independence in 1921 the post-boxes were retained, even the postage stamps were retained with overprints for some time. Now the post-boxes are painted green, but the royal insignia can be clearly seen. The ones I have come across are those of Edward V11, this was Queen Victoria’s son who reigned from 1901 until his death in 1910. When I saw these it struck me as to how short a time we have been out on our own as a Country.

Sometimes I get the feeling that we can lack confidence and belief in ourselves as we are a small nation on the outer edges of Europe. In the early 1920’s when our first independent Government looked around at what they had to start with, they realised that they had very little. In the previous centuries of colonisation we had become an agricultural market garden to feed Britain and its Colonies. The Industrial Revolution was never allowed to reach us and apart from some areas in the Northern part of the Country there was no industrial base in the South of the Country at this time. However, with a strong innovative spirit that launched and developed projects like Ardnacrusha, Shannon Airport, Bord na Mona and the attraction of a Multinational Industrial base we have achieved a great deal in the past 100 years, and we should be very proud of this.

Yes, we were certainly restrained during the colonial period but if we journey upstream a bit in time we will find an Irish people with a great economic and cultural tradition that has helped the advance of civilisation in a global context. In the Monastic period we travelled extensively throughout Europe, providing the people in these areas with learning and religion. Newgrange was constructed over 5000 years ago, in advance of the Egyptian pyramids, by an Irish race that had a knowledge of trigonometry. We also produced intricate and priceless works such as the Book of Kells, the Ardagh Chalice and knowledge of navigation may have seen St. Brendan reach Newfoundland as early as the 6th century. We have also produced literary giants such as Swift, Yeats, Shaw, Wilde, Joyce, Beckett and Heaney that are now globally quoted and respected.

Not bad for a small island country at the edge of Europe. There will be little downsides from time to time, but if we formulate an economic policy that develops value added and innovation over volume manufacturing ,and that also embraces the agricultural, fishing and leisure industry, our future is guaranteed to be very bright and long lasting. As a nation of around 5 million people we have

hosted the European Presidency representing a landmass of over 450 million people. This should not surprise us, we will never be a huge player but we can certainly be a very effective smaller one.

‘The possibility of the Future far exceeds the accomplishments of the Past’ – Thoreau

taken from Corrib News Autumn/Winter 2021

No Comments

Add a comment about this page