Oughterard: The Local Landlords

The parish of Oughterard and its vicinity was owned by a small number of landlords. The oldest, the O’Flahertys, had been in the area since the middle of the 13th century. The largest, the Martins, had been there since the middle of the 17th century. Others, the French St. Georges, Hodgsons and the Doigs came later, the latter two to buy out the land of those landlords who had become bankrupt during the Famine. The estates and townlands owned by the landlords and the head tenants who occupied them are given in the Griffith Valuation for the parish of Kilcummin, 1855.

The landlords of Oughterard before the Famine were all resident. The O’Flahertys, the Martins of Ross and Ballinahinch and the St. Georges were originally Catholic but conformed to the Protestant or State church during the Penal Laws of the 18th century in order to hold on to their estates.

The chief landlords of the parish in the 19th century were the following:

Thomas B. Martin – Ballinahinch Castle

Richard Martin – Clareville, Oughterard. 200,000 acres.

Henry Hodgson – Currarevagh House, Oughterard and Merlin Park, Galway. 17, 064 acres.

Christopher St. Gorge and Arthur French St. George – Clareville Lodge, Oughterard and Tyrone House, Kilcolgan. 15, 777 acres.

John P. Nolan – Ballinderry, Tuam and Portacarron, Oughterard. 6,886 acres.

Robert Martin – Ross House. 5,767 acres. Trustees of Robert Martin, Jnr. 1,789 acres.

Thomas H. O’Flahertie and G. F. O’Flahertie – Lemonfield, Oughterard. 4,500 acres.

Edmund O’ Flaherty – Gurtrevagh, Oughterard. 2,091 acres.

Colonel John Doig and Helen Doig – Clare, Oughterard. 1,445 acres.

George Cottingham – Corribview, Oughterard. 1,140 acres.

James E. Jackson – Kilaguile, Rosscahill. 1,062 acres.

After the Famine the following landlords became owners of the large Martin estate of almost 200,000 acres:

The Law Life Insurance Society – London. Absentee landlords (1852-1872). 190,000 acres.

Richard Berridge and Richard Berridge Junior – Ballinahinch Castle (1872-1915). 160,000 acres.

There were other smaller landlords and middlemen between the head landlord and the tenants in Oughterard and its vicinity:

William D. Griffith – Glan

James O’Hara – Moyvoon

George Thomas – Ard and Ardnasalla

J. Sparrow – Galway and Ard

The Regans – Rusheeny

Edward Archer – Agent of the Law Life Society

The Martins

Thomas Barnwell Martin – Ballinahinch Castle

Richard Martin – Clareville, Oughterard

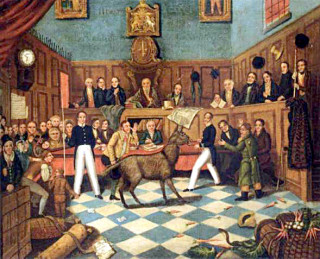

Richard Martin with the donkey in an astonished courtroom, leading to the world’s first known conviction for animal cruelty

The Martin family first came to Ireland with the Normans, possibly with Strongbow in 1169. They settled in Galway in the early 13th century as one of the Galway merchant families called the Tribes of Galway. After the Cromwellian confiscations of the mid-17th century, they became owners of large areas of Connemara or Iar-Chonnacht, which had formerly been owned by the O’Flahertys. In 1698, ‘Nimble Dick’ Martin, the founder of the Ballinahinch branch of the family, was confirmed in the possession of his Connemara estate, known as the Manor of Claremount, by King William III. This grant or patent led to the founding of the town of Oughterard. The early generations of the Martins lived at Dangan, near Galway city and at Birch Hall on the shores of Lough Corrib. Most of the land of the estate of about 200,000 acres consisted of bog, mountain and lake. It extended from outside Galway to Ballinahinch and along the coast to Clifden in Connemara. It consisted of 93,000 acres in the barony of Moycullen and a large number of townlands in the parish of Oughterard.

Richard Martin (1754-1834), known as ‘Humanity Dick’, a noted MP in the Irish and UK parliaments, founded the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1824 and was famous for his skill as a duelist. When Richard inherited the estate on the death of his father Robert in 1794, there were debts of between £20,000 and £30,000 on it. The estate brought in £10,000 a year in rents, kelp and fisheries. His extravagant lifestyle, lavish hospitality and poor estate management increased his debts. The Martins were regarded as good landlords, popular and generous to their tenants. No widow was ever asked for rent and evictions never took place there. Rent was often accepted in kind i.e. labour, turf etc. rather than cash, according to the biographer of Richard Martin. But the Martins did not improve the estate or the condition of their tenants to any great extent. Edward Wakefield, an agriculturist, wrote in 1808 that Richard Martin was the largest landowner in Ireland and Britain and was a constant resident on his estate, but “his estate remains in a state of nature and exhibits every mark of the most wretched cultivation or rather no cultivation at all.” A witness who gave evidence to the Poor Inquiry for the parish of Kilcummin 1835-36 stated that up to the year 1825, Mr. Martin supported most of the poor of the town of Oughterard but after that time he did not reside there and now they had no chance of that kind. Richard Martin lost his seat in the Westminster parliament in 1826. In 1829, he fled to Boulogne in northern France to escape his creditors and died there in 1834.

Thomas Barnwell Martin (1776-1847), MP for Galway 1834-47, inherited the heavy debts of his father’s estate. There were charges of £60,345 on the estate in 1824. He added to his debts by continuing the extravagant lifestyle of his father. But he was a better landlord than his father, resided permanently at Ballinahinch, and developed the district around by tree planting. In 1818, he obtained a presentment for a road between Oughterard and Clifden, which ran through his estate. This road, which replaced an old bridle path, was completed in 1834 and gave employment to the poor as a relief work. During the Famine, the Martins spent large sums in food and clothing for the poor and gave work to hundreds of labourers on their estate. Thomas B. died of fever, caught while visiting his tenant, as a guardian in the Clifden workhouse in April 1847. Both the Tuam Herald and the Galway Vindicator praised Thomas B. Martin as a landlord in their reports on his death. The Tuam Herald of 1st May, 1847, described him as “a good landlord, a conscientious and upright man.” Violet Martin of Ross House wrote that “our kinsman Thomas Martin of Ballinahinch fell victim to the famine fever. He was buried in Galway, 40 miles by road from Ballinahinch, and his funeral followed by his tenants was two hours in passing Ross gate.”

Thomas’ only daughter and heir, Mary Martin (1815-50), Princess of Connemara, inherited a heavily indebted estate. She married her cousin, Arthur Gonne Bell Martin, in 1847. She wrote several novels. Her best known, Julia Howard, gave an account of the ravages of the Famine in the West of Ireland. Bankrupt, she went to New York to better her position and died there in poverty in November 1850. The estate was mortgaged to the Law Life Society of London, absentee landlords, who took possession of it in 1852. Out of 200,000 acres, the Martins were unable to retain a single rood. James Martin of Ross House, a cousin and trustee of the estate, told a parliamentary committee in April 1849 that “the Martin estate of 200,000 acres is in a state of the most deplorable destitution, five-eights of the estate is waste and the property is heavily charged with debts.” Mr. and Mrs. S. C. Hall, travel writers who visited Ballinahinch Castle in 1853, after the end of the Martin family, wrote that “it was at Ballinahinch Castle that the boundless and reckless hospitality of the Martins sapped and eventually destroyed the most extensive property owned by an untitled gentleman in Europe. Every acre of land had passed away from the family, before the last of the race died in absolute poverty in America and among strangers, an heiress and a lady of great ability, some three or four years ago.”

Henry Hodgson – Currarevagh House, Oughterard and Merlin Park, Galway

The Hodgson family came to Ireland from Whitehaven, Cumberland, England. They became mine owners in Arklow, Co. Wicklow before they moved to the West of Ireland in the mid-19th century. Henry Hodgson bought a number of estates in Co. Galway from landlords who had become insolvent and had to sell part of their lands after the Famine. These included G. F. O’Flahertie and C. St. George of Oughterard and other Galway landlords. The Hodgsons mined copper and lead on their estate, mainly in Glan near Lough Corrib in the parish of Oughterard and Hodgson was regarded as an improving and enterprising landlord. Where he bought land, he gave employment and improved the condition of his tenants in Merlin Park (marble quarries) and Glan, Oughterard. His seat at Currarevagh House, Glan, was built in 1842. He owned eleven townlands in the parish of Kilcummin at the time of the Griffith Valuation (1855), some of them shared with William D. Griffith, another landlord in Glan. In 1876, he owned 622 acres in Oughterard and 17,064 acres in Merlin Park, Galway. Sir William Wilde wrote in 1864 that “at Glan near the lake margin is Currarevagh, the seat of Henry Hodgson Esq., the planting on which is beginning to give a civilized look to the brown bogs along the water’s edge.” Hodgson had a mine in Glan and Maam which produced copper and nickel in the 1850s. Men and women worked in the mine and the mineral ore and copper was carried by a steamer to be smelted in Galway and exported abroad. In 1853, a steamer called the Enterprise, owned by the Hodgsons, carried passengers and cargo between Galway and Oughterard. Oughterard pier had been built in 1852.

Mr. H. Hodgson and his sons played an active role in the development of Oughterard, its tourism and fisheries, in the 19th and early 20th centuries. From 1890-95, Mr. H. Hodgson was Vice-Chairman of the Oughterard Workhouse Union. Henry and Dudley Hodgson regularly attended as guardians of the Oughterard workhouse and Rural District Council meetings. Henry, as Justice of the Peace, attended the fortnightly Petty Court sessions at Oughterard. The Hodgsons were active in the development of the fisheries and navigation of Lough Corrib. Among the stewards of the Corrib Regatta at Baurisheen on the 7th August, 1899, were Mr. Henry Hodgson and Dudley Hodgson. Henry Hodgson was the first secretary of the Corrib Fisheries Association, formed on June 1st, 1898. By 1906, the Hodgsons, Henry and Dudley, had held on to their estate and the islands in Lough Corrib in the rural district of Oughterard. By this time, Richard Berridge Junior had begun the sale of his estate in Oughterard and Connemara and the St. George estate in Oughterard had been sold.

Folklore

The Schools Folklore Collection (1937-38) for Glan school was written in Irish. It stated that Mr. Hudson and Griffith (Fearamháin) were the landlords in Glan long ago and their descendants are there still. They remained there during their lifetimes. They were not too hard on the people and it’s said that not too many were dispossessed of their lands. Those who were evicted went to England or built a house up in the mountains. There are a lot of old ruins of houses up in the mountains. It is said that it was the bailiffs or agents who evicted the people. They came at night, broke the doors and took the stock and cattle. There was often fights between the agents and the farmers.

The St. Georges

Arthur French St. George and Christopher St. George – Tyrone House, Kilcolgan and Clareville Lodge, Oughterard

This Norman-French family (originally De Freynes) came to Galway in the early 15th century and were one of the Galway Tribes. John French became Mayor of Galway in 1538. The French family acquired estates in Co. Galway and Connaught in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. They conformed to the State or Protestant church in the 18th century to hold on to their estates and enter parliament, public service and the professions, because of the Penal Laws. The Frenchs adopted the title St. George in 1774. Their seat was Tyrone House, Kilcolgan in south Galway. Arthur French St. George owned Kilcolgan Castle in the 1830s. The branch of the family in Frenchpark, Co. Roscommon produced Field Marshall Sir John French, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1920. In the 18th century, the Frenchs had an estate in Portacarron, two miles east of Oughterard town. In 1829, Francis French owned Portacarron and eight islands on Lough Corrib. In the early 19th century, the St. Georges owned large estates in the baronies of Moycullen and Ballinahinch, Connemara. In 1829, A. F. St. George was landlord of the townlands of Clare, Eighterard, Magheramore, Ard, Ardnasalla, ??? and eight islands on Lough Corrib in the parish of Oughterard. His seat was Clareville Lodge. Thomas B. Martin had settled permanently at Ballinahinch Castle at that time.

Christopher St. George (1810-77), Arthur’s son, was High Sheriff and MP for the county

(1847-52). In September 1836, Robert Graham, a Scottish landlord and traveler who visited Oughterard, said that the great bulk of the property about the place belonged to Mr. C. St. George of Tyrone House. In 1844, A. F. St. George was described as the proprietor of the town. A survey of 1844-45 stated that “near a series of rapids is Clareville, the lodge of A. F. St. George, adjoining Oughterard on the west, the proprietor of the town.” At the time of the Griffith Valuation (1855), C. St. George was landlord of the townlands of Carrowmanagh, Clare, Eighterard. Part of the town of Oughterard, Main Street and part of Barrack Street was owned by C. St. George and the rest of the town by G. F. O’Flahertie of Lemonfield.

There were heavy debts and charges on the St. George estate and he advertised part of his estate for sale, including most of the town of Oughterard, in the early 1850s. Henry Hodgson and Colonel John Doig of Oughterard bought portions of the St. George estate in the Encumbered Estates Court (1849-58), which sold bankrupt or insolvent estates. In 1878, the St. George family owned 15,777 acres valued at £4,533 in Co. Galway. By the early 1900s, the St. George estate in Oughterard parish had been sold. Mr. C. St. George, a Protestant, contributed £50 for the building of the new Catholic chapel in Oughterard, which Fr. J. W. Kirwan p.p. opened in 1830. Later, he gave a site on his estate for a chapel and a school in Glan, and sites for other schools in the parish. At that time, Rev. A. Dallas was establishing proselytising Irish Church Mission schools in the parish. The Galway Mercury of 27th July, 1850 praised Mr. C. St. George for his Protestant liberality, which they said showed that the majority of the Protestant gentry did not support the ‘Jumpers’

Evictions

There were three notorious landlords who evicted tenants in Co. Galway during the Famine: Mrs. Gerrard, Mountbellew; Patrick Blake, Tully, Spiddal; and C. St. George, Tyrone House and Oughterard.

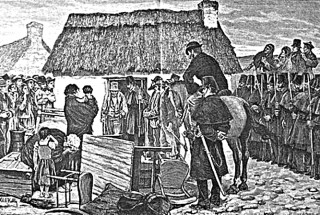

Mr. C. St. George was the only landlord who had an estate in Oughterard who evicted tenants during the Famine. Mr. St. George served notice of eviction on about 600 of his tenants and a wholesale clearance took place on his estate in Lettermore and Garumna in the parish of Kilannin during the Famine in 1844-48. Tenants were also driven from two villages in Oughterard parish, Gortrevagh and Cloosh, by St. George’s agents. It was said that they had been ejected without a rag to cover them. A correspondent for the Galway Mercury wrote in June 1848 about the misery occasioned by the eviction of about 30 families, averaging about four to five members, together with the tumbling down of their cabins and the depopulation of the village of Gortrevagh on St. George’s estate. St. George was regarded as an improving landlord, who evicted tenants to consolidate his estate and to get rid of smallholders to create larger farms. Mr. St. George defended his position when charged with evictions as an MP in the House of Commons in April 1848. He said that he had put £2,500 into the improvement of his estate in Connemara. He had not received any rents and paid an enormous Poor Rate. He paid £50-60 weekly to give employment to his tenants. He said, “I feel indignant at being called a bad landlord or to have failed in any dereliction of my duty.”

Major McKie, Poor Law Inspector of the Galway Union, held a sworn inquiry on February 14th, 1848, on the evictions of Mr. C. St. George and Mr. Patrick Blake of Spiddal in the Galway Union. He sustained the charge that large-scale evictions had taken place in south Connemara and Oughterard on the estate of Mr. C. St. George by his agents at the height of the Famine. Mr. C. St. George died at Tyrone House, Kilcolgan, in 1877. His evictions during the Famine were forgotten by his tenants. A thousand of them walked behind the coffin all wearing mourning bands and hatbands.

The Nolans

John P. Nolan – Ballinderry, Tuam and Portacarron, Oughterard

Most of the estate of Colonel Nolan was in Ballinderry, Tuam, but he had a small estate in Portacarron, Oughterard. Francis French owned the land and estate at Portacarron in the early 19th century. Samuel Lewis, in his Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1837), described Portacarron of J. Nolan Esq. as one of the principal seats in the parish of Kilcummin. In a survey of 1844-45, Mr. Nolan’s seat was given as Portacarron, situated south of Oughterard and near Lough Corrib. In the Griffith Valuation of 1855, Marianne Nolan owned Portacarron and some islands on Lough Corrib. It consisted of 233 acres with 18 tenants on the estate. The Nolan family also owned Derryeighter, which consisted of 877 acres. In 1876, John P. Nolan had an estate of 6,866 acres.

By 1906, the Nolans did not own any land in Oughterard rural district. In that year, Mary Browne of Galway was the owner of Portacarronbeg, consisting of 49 acres. This townland was owned by Colonel Anderson in 1855. According to the Schools Folklore Collection (1937-38), the Regans of Rusheeney bought Portacarron after the Nolans. They were good landlords and did not evict their tenants.

Boats carried turf to Galway from Portacarron in the 19th century. Portacarron contains an early ecclesiastical settlement, close to the shore of Lough Corrib, referred to by Sir William Wilde in 1867 as the church of Portacarron near the edge of the lake. The enclosure contains a church and the ruins of an early Christian oratory.

The Portacarron Evictions

The worst evictions around Oughterard took place at Portacarron, owned by John P. Nolan. The whole townland with its tenants was evicted between 1864 and 1866. They were given £50 by the local people to start a new life in some other place. Capt. Nolan stood as a Liberal and Home Rule candidate in an 1872 by-election in Co. Galway. He was opposed by William Le Poer Trench of Ballinasloe, a Conservative who represented the landlord interest. A most serious objection was raised against Capt. Nolan by Fr. Dooley, a Catholic priest in Oughterard. Nolan was charged with having evicted fourteen families, consisting of 90 persons in all, from his estate in Portacarron from 1864 to 1866. Two of them had since died in the Oughterard workhouse. Fr. Dooley published a full list of the names of those evicted in the Galway Vindicator on 15th February, 1872.

Capt. Nolan admitted the substance of the charge made against him. The only way he could go forward for election was to submit his case to an arbitration process, rather than defending his position in the courts. The arbitration took place at Oughterard on 29th May, 1872. It’s three members were sympathetic to the tenants and decided that the tenants should be restored to their lands and given compensation. Capt. Nolan accepted this decision of the arbitrators, although nothing had been done for the tenants in the meantime. In the 1872 election which followed, Nolan easily defeated Trench but was afterwards unseated because of undue clerical influence on his side. In the 1874 election, Capt. Nolan was elected as a Home Rule MP for Galway, as was Mitchell Henry of Kylemore Castle, Connemara. The Portacarron case had created a precedent, as it was the first case in post-Famine Ireland that a landlord was prepared to abide by a decision of arbitration so that it was legally binding on all concerned. The tenants welcomed the decision, as they were restored to their original farms or received compensation. Landlords saw it as a betrayal of their position, as they felt they would not get justice in future disputes.

The Martins of Ross

Robert Martin and James Martin – Ross House, Kilannin

The Martins of Ross were of the same family originally as their cousins of Ballinahinch and could trace their origin to the Norman conquest of Ireland in the 12th century. They settled in Galway in the early 13th century and became mill owners and one of the Galway merchant families called the Tribes. They were the first of the Tribes of Galway to venture out into the wild country of the native Irish. Robert Martin, who was High Sheriff and Mayor of Galway, bought an estate from the O’Flahertys at Ross in 1590. His grandson, Robert Martin, High Sheriff of Galway in 1644, supported the cause of King Charles I against Cromwell and Parliament in the mid-17th century. At the capture of Galway in 1652, he was dispossessed of his property and house in the city by the Cromwellians and built a house at Dangan, outside the city. He received a grant of 2,909 acres in the barony of Moycullen by Royal Patent on 21st August, 1677 and died in 1700. The Martins of Ross were the senior branch of the family. Robert’s son, Richard ‘Nimble Dick’ Martin, produced the junior or Ballinahinch branch of the family. Robert Martin (d. 1868) and his son James (1804-72) were the landlords at Ross in the 19th century and during the Famine. Robert Jasper Martin (1846-1905), son of James, owned the estate until his death in 1905. The family were made famous in the late 19th century by the literary works of Violet (Florence) Martin, who wrote under the pen name Martin Ross, and her cousin Edith Sommerville. They wrote books about the Anglo-Irish view of Irish life, i.e. The Irish R.M. stories and The Real Charlotte etc.

Sir William Wilde described the Ross estate in 1867. He wrote that the next object of note along the main road from Oughterard to Galway “is the extensive, well-wooded and picturesque Demense of Ross, the property of James Martin Esq., on the northern or left-hand side, with the pretty lake anciently called Lough Lonan, in an island of which there are still some vestiges of the old castle of Ochery.” The Martins of Ross were relatively small landlords compared to their cousins of Ballinahinch and Clareville, who had a vast estate of 200,000 acres in Connemara. Robert Martin owned 5,767 acres, valued at £1,326 in 1876. Most of their land was in the parish of Oughterard [at?] Callinamuck etc.

The Martins were originally Catholic and Jacobite and supported the Stuart cause. During the Penal Laws of the 18th century, they became Protestant but they were tolerant of the Catholic religion as they lived in an entirely Roman Catholic district. Ross House was burned down in 1740 and was rebuilt and replaced by the present building about 1777, “a tall unlovely block of great solidity” which suggested the idea of defence, according to Violet Martin of Ross. It withstood the ‘Night of the Big Wind’, 6th January, 1839, when all the cabins around it were destroyed. Mrs. J. M. Callwell, who wrote a history of the Martins of Ross, wrote that her grandfather Nicholas said that “if Ross fell that night, no house in Ireland would stand”. Ross House was again burned down in 1932. James Martin was the first Chairman of the Oughterard Workhouse Union when it was established in October 1849. The Martins were active in relieving the misery and destitution of the large number of tenants on their estate during the Famine. In 1847, a soup kitchen was set up at the gates of Ross House to relieve their starving tenants. According to Violet Martin, “Impossible to feed, impossible to see unfed.” Good relations existed between the Martins of Ross, as landlords, and their tenants. Arrears of rent were given time to be taken by the boatload of turf or worked off by day labour and evictions were unheard of. This was the view put forward in Irish Memories by E. Sommerville and Violet Martin.

The Martins incurred heavy debts and never really recovered from the effects of the Famine but managed to hold on to their estate. James Martin had to go to London to work as a journalist “to tide over the evil times”, according to his daughter Violet Martin. After the death of James Martin in 1872, the Martin family left Ross for Dublin and did not return until 1888. Robert Jasper Martin, who had inherited the estate, went to London to work as a journalist and only returned to Ross House occasionally. While they were absent, a new agent took charge of the estate. His policy led to bitterness, discontent and evictions of tenants. About 1875, all the tenants of the townland of Porridgetown, which belonged to the Martins, were evicted from their homes to the side of the road. They lived in little huts and charitable people gave them food and lodgings. Fr. Coyne, p.p. of Kilannin, got them back in to their houses again – his house to this day is called Land League House. In January 1880, a process server from Galway served notices of eviction on 30 families on the Martin estate in a single day. He was protected by a hundred constabulary from Galway and a force of local police from Oughterard. A large crowd gathered to prevent the serving of the eviction notices but failed because of the great forces against them. Some violence broke out.

The Martins advertised the sale of the estate in the Landed Estates Court in May 1885. In 1888, Violet (Florence) Martin returned to Ross House and tried to pull it back from ruin and decay after sixteen years of neglect. After that, the Martins lived as tenants on the estate. Robert Jasper Martin, the last owner of the estate, died in 1905. Various Martins lived at Ross until 1914. Violet Martin died in 1915. The estate was divided up among the tenants in the early 20th century. Ross House was sold to Claud Chevasse in 1924.

The O’Flaherties – Lemonfield, Oughterard

The O’Flahertys were an old Irish family who ruled over a large territory east of Lough Corrib, i.e. the barony of Clare, before the Norman conquest of Connaught in the early 13th century. In the mid-13th century, they were driven westward across Lough Corrib into the area known as Iar Chonnacht, or the barony of Moycullen, by the Norman de Burgos (Burkes). They soon controlled the whole of Connemara, which they ruled over undisturbed for about 400 years, from 1250 to 1650. They built stone fortresses in the new territories they occupied, the most notable was Aughnanure Castle near Oughterard. They also built castles in the late 15th century at Moycullen and along the sea coast at Bunowen, Ballinahinch and Renvyle. The O’Flahertys of Lemonfield were descended from the Aughnanure branch of the family in a direct line from Murchadh Na dTuadh, their greatest chieftain in the 16th century. During the 17th century Cromwellian confiscations, the O’Flahertys, who had sided with the king, were dispossessed of all their lands, which were soon taken over by the Martins of Ballinahinch, a Norman family and one of the Galway Tribes. By 1618, their territory had shrunk to 500 acres situated in the parish of Kilcummin or ??? which was their ancient inheritance. In the 18th century, the O’Flaherties conformed to the Protestant or State church to keep their small estate undivided.

Sir William Wilde gave a description of the seat of the O’Flahertys when he visited Oughterard in 1867. He wrote, “at the eastern extremity of the town is Lemonfield, the seat of G. F. O’Flahertie Esq. (whose ancestors occupied so much of this territory and performed so notable a part in the history of West Connaught for many centuries). The house stands in a spacious lawn reaching down to the lake and is surrounded by well-grown timber and highly cultivated gardens and pleasure grounds.” Aughnanure Castle, which was occupied by the O’Flahertys from the 16th to the early 18th centuries, was described as “a castle in ruins” in late 18th and 19th century accounts.

Sir John O’Flaherty (1728-1808), who lived at Lemonfield, was a Justice of the Peace and High Sheriff of Galway in 1800. He died in 1808 at Lemonfield, aged 82, and was buried in the adjoining mortuary chapel of Kilcummin cemetery, like generations of his ancestors.

The O’Flahertys had ruled over an area on which the city of Galway now stands, as well as a large area east of Lough Corrib, before the Norman conquest of Connaught in the 13th century. They were thus enemies of the citizens of Galway, all the Norman Tribes who had driven them out of their territory, and made frequent attacks on the city in the early centuries. It is little wonder the citizens prayed “From the ferocious O’Flahertys, O Lord deliver us”, which was inscribed on the west gate of the city. When the young French nobleman De Latoenage visited Sir John O’Flaherty at Lemonfield in 1796, he received a warm and charming welcome and found him “anything but ferocious”. Sir John provided him with a horse to travel to Richard Martin at Ballinahinch, as there was no road. Capt. Thomas Henry O’Flahertie, born 1777, Sir John’s son, and George (G. F.) were the landlords at Lemonfield in the first half of the 19th century and during the Famine. In 1837, Capt. T. H. O’Flahertie Esq., Lemonfield, was described as one of the principal seats in the parish of Kilcummin. By 1855, the O’Flaherties owned 16 townlands in the vicinity of Oughterard town. Part of the town was owned by the O’Flaherties and the rest by St. George of Clareville Lodge. The O’Flaherties owned the tolls and customs of the fair of the town of Oughterard. With the death of Thomas B. Martin of Ballinahinch during the Famine in April 1849, the O’Flaherties became the landlords of Oughterard. Due to debts, part of their estate of 4,500 acres was sold to Colonel John Doig and Henry Hodgson, local landlords, in 1854. The O’Flaherties had a reduced acreage of 2,346 acres in 1864. The rental on the estate included the lead mines of Glengowla, four miles west of Oughterard, and the black marble quarry near the town. In 1876, Theobold O’Flahertie of Lemonfield was the owner of an estate of 2,340 acres, valued at £604-5s-0d, in the vicinity of Oughterard. By March 1916, the O’Flaherties had accepted offers from the Congested Districts Board for the sale of part of their estate.It does not appear from newspaper reports or other records that the O’Flaherties of Lemonfield evicted tenants during the Famine or in the later 19th century.

Witnesses who gave evidence to the Poor Inquiry of 1835-36 for the parish of Kilcummin stated that some local landlords charged exorbitant rents for poor quality land and that some of them were cruel towards their tenants. Dr. Kirwan p.p., Oughterard, gave evidence that if the tenants improved their land or house, the landlords would raise the rent. Capt. T. H. O’Flahertie said that in times of distress, landlords would give relief and provisions to tenants in need, but strictly on credit, to be paid back in a separate account from the rent, and that landlords never lost anything in that transaction. He said the resident landlords gave some employment; he employed ten to twenty of his own tenants who held under leases of 10 shillings an acre.

In one respect, the O’Flaherties of Lemonfield would have been unpopular with the Catholics of the parish. When Dr. Kirwan was appointed parish priest in 1827, he said that there was no house of worship in the parish of 10,000 souls. He built a beautiful new church, a parochial house and a dispensary for the district. Some years later, Mr. G. F. O’Flahertie challenged his right to the lease of the ground on which the church was built, claiming it was his own. Dr. Kirwan eventually won his case, with the assistance of T. B. Martin, and the church was dedicated and finally opened in 1837. In addition, the O’Flaherties gave active assistance to the proselytising movement of the Rev. A. Dallas of the Irish Church Mission Society, who were active in the parish during the Famine and for many years afterwards. They were trying to induce the Catholics of the parish, in great distress and hunger, to become Protestant. Two of the four proselytising schools of the Rev. A. Dallas in the parish were under the control of G. F. O’Flahertie of Lemonfield, i.e. the schools at Clare and Glengola.

The O’Flaherties played a prominent part in the public life of the town and parish of Oughterard during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Thomas H. O’Flahertie was Chairman of the local Relief Committee during the Famine in 1846-47. He worked with many others, clergy and lay people, in providing relief for those in greatest need. George F. O’Flahertie became Chairman of the Oughterard Workhouse Union in 1851. The O’Flaherties were active as officers and guardians of the Oughterard workhouse throughout the 19th century, i.e. George, Edmund, Theobold and Jack (John P.). Jack O’Flahertie was Vice-Chairman of the workhouse Union in 1906. From the 1880s, he was active in the development of the town and parish. He regularly attended meetings as a workhouse guardian, of the Rural District Council, school attendance meetings and acted as a magistrate in the fortnightly Petty Court sessions. He was active in the development of the fisheries on Lough Corrib. He lived at Lemonfield House and died in the 1930s, the last member of the family.

The original territory of the O’Flahertys, on the eastern shore of Lough Corrib, was described under the name Hy Briúin Seola and Muintir Murchadha was their ancient tribal name. The name was originally spelled O’Flaherty, later O’Flahertie, in old [pat?] as O’Flahertie. Their motto was Fortuna Favet Fortitus (Fortune favours the brave).

Edmund O’Flaherty – Gortrevagh, Oughterard. 2,091 acres.

Edmund O’Flaherty was a landlord and inn-keeper based in Gortrevagh townland, Oughterard. He belonged to the Renvyle or Western branch of the O’Flaherty clan.

In the 18th century, the O’Flahertys held lands from the Blakes of Renvyle, barony of Ballinahinch, which they had previously owned. Henry Blake, one of the Galway Tribes, did not renew the lease in the early 19th century, as he decided to live there himself. The O’Flahertys moved and bought land in Oughterard and Moycullen. To the same branch of the O’Flahertys of Renvyle belonged Anthony O’Flaherty of Knockbane, Moycullen, MP for Galway city from 1847-59, who played such a notable part on behalf of the poor during the Famine. Edmund O’Flaherty of Gortrevagh remained a Catholic, as did Anthony O’Flaherty, unlike the O’Flaherties of Lemonfield, who conformed to the Protestant or State church. The branch settled at Moycullen also produced the noted 17th century historian Roderic O’Flaherty (1629-1718), who was reduced to poverty by the Williamite confiscations of the late 17th century. Edmund O’Flaherty had been High Constable for the barony of Moycullen from 1824-29, which he said enabled him to collect the full amount of tithes and taxes in every townland of the parish of Kilcummin.

Under the new Poor Law Act (1838), all occupiers of land had to pay a tax called the Poor Rate for the support of the poor in times of distress. This had become a heavy burden during the Famine, as the workhouses began to fill. O’Flaherty had been Poor Rate collector for the parish of Kilcummin but resigned his position in 1843, as the Poor Rate had become so unpopular and difficult to collect. In the same year, there was a riot in Oughterard and Kilannin in opposition to the Poor Rate, as the small farmers and peasants were unable to pay the Rate. The government had to bring down an outsider from Dublin, George McDonald, to enforce the Poor Rate with constabulary and military protection, during the Famine. In 1855, Edmund O’Flaherty owned two townlands in the parish of Ballinakill and Omey, near Clifden, and was landlord of the townlands of Gortrevagh and Ardnasalla in the parish of Oughterard. The Willis family became the later owners of Gortrevagh, where the present Oughterard Golf Club is situated. Thomas Colville Scott, an Englishman who visited Oughterard in February, 1853, described Edmund O’Flaherty as “a postmaster, inn-keeper, farmer and papist.”

O’Flaherty was land agent for Christopher St. George, who owned a large estate in Oughterard and south Connemara. In June, 1848, evictions took place in the townlands of Cloosh and Gortrevagh on the St. George estate. The Galway Mercury of June, 1848, wrote of the evictions of 30 families, the tumbling down of their houses and the depopulation of the village of Gortrevagh in Oughterard. In 1864, Edmund O’Flaherty was a tenant of Captain O’Hara, a local landlord in Moyvoon, who owned Aughnanure Castle. Sir William Wilde, a regular visitor to the area, wrote in 1867 that Edmund O’Flaherty was a descendant of the Moycullen branch of the family and was at that time utilising the Castle and manor as a dairy farm. O’Flaherty became Vice-Chairman of the Oughterard workhouse Union when it was established in October, 1849, and became its Chairman in 1875. In 1876, Edmund O’Flaherty J.P. (Justice of the Peace) owned 2,091 acres, valued at £314. The Galway Vindicator of January, 1880, reported that Mr. Edmund O’Flaherty was the only local landlord in the parish who was not an absentee at a time of great distress during the Land League crisis (1879-82). In 1906, Mary D. Willis occupied Gortrevagh, consisting of 158 acres.

Colonel John Doig – Clare, Oughterard

Colonel John Doig was from Edinburgh, Scotland and had been involved in the British East India Company. The Doigs came to Oughterard around the time of the Famine and were based in Clare townland. They were still there in the late 1930s. Colonel John Doig bought 2,153 acres for £5,040 from the sale of the St. George estate in the early 1850s. It is not clear where this land was, as C. St. George had an estate in different parts of Connemara and in the barony of Clare, north Galway. In 1855, John Doig owned 1,445 acres in the parish of Oughterard, which included the townlands of Clare, Annakeelaun, Ard, Magheramore and some islands on Lough Corrib. These lands were possessed by Arthur F. St. George, the father of C. St. George, in the 1820s. The home of John Doig and his family was occupied by George Cottingham, a local landlord, in 1855, who held it from John Doig. It is now a Bed and Breakfast. Colonel John Doig was member of the Oughterard Relief Committee in 1862-3, at a time of economic distress and food shortages in the parish. He was praised for his contribution as a landlord to the poor of Oughterard by Fr. Michael Kavanagh p.p. (1852-64). He was a magistrate and Vice-Chairman of the Oughterard workhouse Union in 1862. He was Deputy Vice-Chairman and a Poor Law guardian of the workhouse from 1858-70. A medical officer of the Union, he died in 1871. His children, Helen, John and Scrope Doig, inherited his estate. In 1876, Helen Doig, Clare, owned 125 acres; John Doig Junior, Clare, owned 391 acres; Scrope Doig, India, owned 929 acres. Scrope Doig owned the townland of Magheramore, consisting of 929 acres, which he still held in 1906.

Scrope Doig took an active part in the development of the fisheries on Lough Corrib and the tourism of the town. The Corrib Fisheries Association was formed in Galway on the 1st January, 1898 to improve the angling on Lough Corrib. Colonel Scrope B. Doig was Secretary of the Association from 1900 to 1910. Before 1900, the number of tourist anglers who visited Oughterard was very small. At a special meeting of the Association in the Angler’s Hotel, Oughterard, on 23rd August, 1907, Scrope Doig said that the tourist anglers had increased very largely in recent years. Although there were three hotels in the town, they did not have sufficient rooms for all the visitors. Scrope said there were now over a hundred professional fishermen who visited annually and both the town and the railway had reaped great benefits as a result.

Folklore

Reports from the School Folklore

Collection (1937-38) from the convent school, Oughterard, stated that Mr. Doig and Jack O’Flaherty were the landlords of Oughterard. It was said that they were not as bad lately as they were in the beginning because the people lessened their power. They had agents and bailiffs under them worse than themselves, who evicted people, some of whom went into the workhouse. They lived a lifetime in this place. In the old times, the landlords were very cruel and they evicted some people even if they paid the rent. Colonel Doig is still alive but Jack O’Flaherty is dead. The landlords had great power over the people but the land was later taken from them by the Land Commission.

James E. Jackson – Kilaguile, Rosscahill and Kilannin

James Edward Jackson (1824-1907) was the son of Rev. James E. Jackson, Rector of Ardee, Co. Louth and later Dean of Armagh. He came from the north of Ireland and in August, 1853, he bought a property in the townland of Kilaguile from Robert Martin of nearby Ross House. He built a house at Kilaguile now known as Ross Lake House Hotel, parish of Kilannin, barony of Moycullen. He was active in local affairs as a Justice of the Peace (J.P.) and an officer and Poor Law guardian of the Oughterard workhouse Union from 1875-1900, acting regularly as its Chairman. In October 1879, Jackson, as Chairman of the Special Presentment sessions, Oughterard, signed a memorial to the Lord Lieutenant, with a list of useful public works for the poor, i.e. a railway from Galway to Clifden, the bridging of Knockferry between Headford and Moycullen and the reclamation of vast tracts of mountain land in the barony of Moycullen etc. Jackson was agent for Robert Martin of nearby Ross House, who was often absent from his estate after 1872. In 1876, James E. Jackson J.P., Kilaguile, Oughterard, was the owner of 1,062 acres valued at £91. In 1906, the year before he died, he held 1,053 acres and a mansion house at Kilaguile. In 1886, he had been agent for Lord Ardilaun (Guinness) of Cong, who was owner of a vast estate.

On October 22nd, 1880, Jackson gave evidence to a Commission on the Land Acts (Bessborough) at the Railway Hotel in Galway. He was examined on his position as a landlord, his relations with his tenants, rents etc. This was the period of the Land League agitation when the tenants under leaders were challenging the landlords and refusing to pay rents. The evidence is from a landlord’s viewpoint. He said he was the owner of land, farmed his own land and was agent for Capt. Martin of Ross. The tenants in his neighbourhood near Lough Corrib were mostly smallholders of land, some of them as low as £2-10s valuation and so poor that if they got the place for nothing (no rent), they could not live on it. In general, the rent was 40-50 percent above the Poor Law valuation of the land and he felt the rent charged was reasonable. Some of his tenants went to England and more to Scotland as labourers; others work on the farms of neighbouring landholders. Most of the tenants had not enough land to live on. They took conacre from large farmers on which, in general, they grow potatoes and some turnips. As a rule, tenants did not improve their holdings and landlords do not encourage them to improve. Sometimes they reclaimed bogland, on which potatoes grow well. Five years ago (i.e. 1875), he drained a lake on the land of which he was agent. As a result, the tenant agreed to pay 1 shilling in the pound of extra rent. When he asked for the added rent, they refused to pay a penny. He served them with a notice of eviction and they gave in. He had been denounced ever since by their priest (Fr. Coyne) for his harsh conduct towards his tenants but he merely asked for what they agreed to.

The tenants had refused to pay any rent this year (1880) unless he reduced the rent by 40-50 percent, i.e. the Poor Law valuation. Last year (1879), he gave a reduction of half a year’s rent, i.e. a 50 percent reduction, as they were very poor and they needed it. He took proceedings in court against twelve tenants who refused to pay any rent and they agreed to his terms and submitted. The people are willing to pay a fair rent but on their own terms as valuators and not what the landlords want. They do not cultivate or farm the land as they should. They are lazy and do nothing during the winter until spring. For the rest of the year, they go to fairs, markets, wakes, weddings and funerals, where everyone attends. He had come from the north of Ireland twenty years ago, where the people are more industrious than here. He had laid out the large sum of £800 during the last twelve years for houses for small tenants and labourers close to his own place, i.e. labourer’s cottages. He had as much difficulty in dealing with them as if they were paying £50 a year. On his own property, he did not charge for turf and they could take as much as they could cut for their own use. When Jackson was agent for Lord Ardilaun in Cong in 1886, he said that of 600 tenants on the estate, the average rent was £7-14s per annum. On his own estate in Kilaguile in 1880, he was charging 40-50 percent above the Poor Law valuation. Rent varies according to farm size and the quality of the land. If the valuation of the holding was £5 per annum, the tenant had to pay a rent of £7 or £7-10s per annum or face eviction. Rents were exceedingly high in some places in Galway in 1880. At a Land League meeting in November 1879, the rent roll of one property in the parish of Kilannin had been raised within the last six or seven years by the enormous amount of one hundred and fifty percent. In five townlands in the parish of Moycullen, the rent was more than doubled between 1870-72 and 1879.

Evidence of the witnesses before the Bessborough Commission in 1881 said that the average rent of small holdings, many of them consisting partly of bog and unreclaimed land, was in the region of £7 per acre in Co. Mayo, Donegal and the west of Ireland, i.e. high rents on small farms.

The Law Life Insurance Society

Thomas B. Martin (1786-1847), MP for Galway, died on 23rd April, 1847. His only daughter, Mary Martin, inherited the estate, which had become bankrupt. Arrears of rent on the estate amounted to £30,000 in October 1848. Mary Martin (1815-50) emigrated to America and died in New York in November 1850, penniless and among strangers.

The Law Life Society of London became the mortgagees of the estate of nearly 200,000 acres. It contained 93,000 acres and over 100 townlands in the barony of Moycullen. On 14th July, 1852, the Law Life

Society, the mortgagees, took possession of the estate at the nominal sum of £186,000. By an order dated 9th November, 1853, the manor of Clare or Claremount at Oughterard was sold to the Law Life Society with all its manorial rights, i.e. the right to hold fairs and markets etc., which had been granted to ‘Nimble Dick’ Martin in 1698 and which led to the founding of the town of Oughterard. Out of the vast estate of 196,500 acres, the Martins did not get a single rood of ground. The Law Life Society was an absentee financial company, based in London. Their land agents based in Connemara were Mr. George T. Robinson and his son, Henry. Lord Campbell, a landlord in Moycullen, was a director of the company and Edward Archer an agent in Oughterard. They immediately embarked on a wholesale clearance of the small tenants off the estate and raised the rents. Travel writers who visited Oughterard and Connemara in the immediate aftermath of the Famine gave accounts of these widespread evictions. The Rev. S. G. Osborne, who visited the area in 1849-50, wrote that from Galway to Oughterard, en route to Clifden, the country was disfigured by the evidence of eviction and the wretched appearance of very many of the people. Dr. John Forbes, who visited the district in 1852, wrote in reference to the Law Life Society that “throughout the whole district, the mark of eviction and depopulation were more extensive and conspicuous” than he had seen in any other part of Ireland. Henry Coulter, a journalist, in his book The West of Ireland (1861-62) gave a detailed account of the activities of the Law Life Society in Connemara. He wrote on 12th December, 1862, that the directors of the Law company were land speculators rather than landlords. They received an annual rent of £10,000 but not a shilling found its way back from the company to the development of the district. The land remained undrained, unfenced and unimproved in any respect. Their sole object, he wrote, was to get as much as possible from the property and to spend as little as possible in return. In the early years, they had raised the rents to an exorbitant rate.

Coulter wrote that, in 1862, a railway had been projected from Galway to Oughterard and the residents were most anxious to have it carried out. The Law Life company had been asked to subscribe to it, as it would pass through, and benefit, their property, but the directors had refused to support it on the grounds that it would not pay. Sir William Wilde wrote in 1867 that the company had brought about no improvements, no drainage, no reclamation and scarcely any planting. He complained that little had been done in the last twenty years to improve the condition of the land or the people, in spite of the great wealth of the Society. The Martins, who had ruled over the district since the mid-17th century, did not evict their tenants, although they were not land improvers. They ruled over the area like absolute rulers or feudal kings but they were indulgent and benevolent landlords towards their tenants. Richard Martin said that the King’s writ (law) did not run beyond his gate lodge at Oughterard to his thirty-mile avenue to Ballinahinch Castle. A travel writer in the mid-19th century wrote that “Colonel Martin (Humanity Dick) is quite a king in his immense domain” and that he “was the best Martin that ever reigned.”

Evictions

The policy of the Law Life Society was to lay out the minimum of improvements on the estate while distressing the tenants by Poor Rates and rents. In 1850, the company served notice to quit on between 500 and 600 tenants. On 20th June, 1851, they announced that proceedings of ejectment (eviction) against 600 tenants had taken place. Their land was let to new tenants who were selected from the best of the old tenants and who could pay the higher rents.

They proceeded with further evictions, 493 in all in 1851. The rents went from £5 to £25 per annum, depending on the size of the farm. They raised the rents yearly from 1850 and used drivers and bailiffs to evict smallholders of land. The Galway newspapers of the early 1850s referred to the evictions of the Law Life Insurance Society as “wholesale extermination and a system of depopulation of Connemara.” Galway city and its workhouse was being swamped by tenants driven out of Connemara by the agents of the Law Life Society.

Evictions in Oughterard

Francis B. Head, an English travel writer, visited Oughterard in 1852. The head constable informed him that four or five months ago, a great many evictions had taken place in the neighbourhood, principally on the Martin property of 170,000 acres, which had been lately purchased by the Law Life Society. He had attended all the evictions but there was no resistance or trouble of any kind. Those who left went into the workhouse, to America or England. The Master of the Oughterard workhouse informed him that on 1st January last, the number of inmates in the house was 972, but that on 29th June, in consequence of evictions, there was no less than 1,475 in the house, of whom 680 had since emigrated or managed to find employment. That would indicate a very large number of evictions, perhaps four or five hundred, and large-scale emigration after the Famine.

The Law Life Assurance Company

Mr. Justice Keogh addressed the Grand Jury of Co. Galway at the Summer Assizes of 1869. He said, “the Law Life Assurance Company, gentlemen, is an absentee who carry on this business in London and who never come to this country. They are the owners of vast estates in this county and in the county of Mayo. Yet they never disturb their repose by contributing to the comfort, or looking to the interest, of their tenants. The term absentee is an odious term – a person who derives his income in one country but resides in another, where he spends the income. The common voice of mankind says that this is an evil and an injustice; it points to lands imperfectly cultivated, labourers inadequately employed, to ruined cottages, to uneducated children; and it proclaims that these things would not be, if the proprietor resided in his estate.”

The Landlords of Moycullen

The landlords of Moycullen in the 19th century and during the Famine were:

George E. Burke – Danesfield, Moycullen. 2,480 acres.

Patrick Blake – Spiddal and Tully. 17, 335 acres.

Anthony O’Flaherty Esq. – Knockbane House. 1,522 acres.

John A. Browne – Kircullen, Moycullen. 590 acres.

Francis Comyn – Drimcong and Spiddal.

J. Kilkelly Esq. – Drimcong.

A. W. Blake Esq. – Furbough, Spiddal.

There were other landlords who owned large estates in the southern part of the parish of Kilcummin, Oughterard and the barony of Moycullen. They resided either in Galway city or the Spiddal area, i.e. Patrick Blake, Nicholas Lynch, Henry Comerford, J. S. Lambert and Martin S. Kirwan. They owned land in Spiddal, Rossaveal, Lettermullen, Carraroe etc. and did not affect Oughterard or its neighbourhood. The Blakes, Kirwans and Lynchs were large landowners and descendants of the Galway merchant families called the Tribes of Galway.

Lord Campbell – Moycullen

Lord Campbell (1779-1861) was MP for Edinburgh and a Chief Justice in England. He became Lord Chancellor of Ireland in 1841. He was a director of the Law Life Company, who had bought the Martin estate. His purchase of an estate after the Famine in Moycullen and Barna gave him 100,000 acres.

Thomas Colville Scott, who surveyed the Martin estate for a prospective buyer in 1853, wrote: “We reached Moycullen village on March 3rd, 1853. In the immediate neighbourhood, we saw a poor widow, with her boy, sheltering in a roofless cabin belonging to Lord Campbell, evening was coming, the ground was covered with snow. She must inevitably perish by morning. An officer in the constabulary barrack said she was waiting till her furniture was taken to the house of a neighbour for shelter for the night. I afterwards heard that Lord Campbell was clearing the whole of his wretched land of squatters, allowing each ejected tenant all arrears of rent and ten shillings when the roof was pulled off their cottage.” Colville Scott said that this was a harsh but necessary measure. Lord Campbell engaged in the consolidation of farms on his estate, i.e. the creation of large farms by the removal of the small tenant holders. This practice was engaged in by many landlords, as when the valuation of the holding was less than £4 per annum the landlords had to pay half or sometimes all of the rates of the tenants. Many of the small tenants during and after the Famine did not pay any rates or rent because they were too poor.

The Galway American newspaper of May 1862 referred to Lord Campbell of Moycullen as a bad landlord who consolidated farms, which led to the eviction of tenants, and who was indifferent to his tenants. In April 1852, Lord Campbell evicted no less than 800 persons in a single week on his Barna property and the houses of the poor people were fired.

The Berridges – Ballinahinch and Oughterard

In 1872, the former Martin estate was bought by Richard Berridge (1813-87), a wealthy London brewer, from the Law Life Assurance Company. He paid £230,000 for the property at a reduced acreage of 160,000 acres. The sale included the castle of Ballinahinch and its fisheries. He held Claremount and the tolls for the fairs and markets of Clareville, Oughterard. The Law Life Company had gained from the property. They had sold 32,000 acres for £75,000 and, from 1860, they were getting £10,000 in rents per annum. Richard Berridge was the son of Capt. Florence McCarthy, formerly from Co. Cork, who had married a Miss Berridge. Richard, who adopted his mother’s name, was born in the West Indian islands. He returned to England and became involved in the Meaux brewing business in London. His seat as a landlord was Ballinahinch Castle, Connemara.

He had a son, also called Richard, who took over the estate after his father’s death. His seat was Ballinahinch Castle and Screebe, Maam Cross. In 1878, Richard Berridge of Great Russell St., London, owned the following estates:

Galway town – 254 acres

Galway county – 159,898 acres

Mayo county – 9,985 acres

Middlesex and Kent – 400 acres

Total – 171,117 acres

Valuation – £8,742

Berridge was the largest territorial landowner in Ireland or Britain. He owned a large number of townlands in the parish of Oughterard and its vicinity, among them the following: Curraghduff, Camus, Glantrasna, Leam, Lettermore, Barrusheen, Claremount, Birch-Hall, Magherabeg, Oakfield, Killola, Thonewee, Srue, Porridgetown West, Gortnagrough, Garrynaghry, Rushveala, Shanafeastin and islands on Lough Corrib etc.

The Galway Vindicator of 10th July, 1872, reported that Mr. Berridge had arrived in Galway to see for the first time his extensive property.

In the last twenty years, Connemara had been depopulated by clearances, evictions and emigration. Livestock had replaced the tenants. Apparently, Berridge had purchased the estate for sporting, fishing and hunting purposes. He had built a number of fishing lodges, including those at Lough Inagh, Fermoyle and Scribe. The territory Berridge had acquired in Connemara was wild and barren, consisting of bog, mountain and lake, with a small portion of it arable land. It contained a large number of tenants, who lived on small farms and in great poverty. Soon after Berridge took over the estate, the land agitation of the Land League began. He was an absentee from the estate during most of this period and his estate was managed by his land agent, George T. Robinson, and his son Henry, who resided at Ballinahinch. The Robinsons were unpopular as land agents and they engaged in large-scale evictions, especially during the Land War of the 1880s, when tenants refused to pay the rents.

George Robinson was shot at more than once but survived as he was armour-plated. A journalist for the Daily News, B. H. Beeker, wrote on the 9th November, 1881, that as he approached Ballinahinch Castle, he saw Mr. Robinson, agent of Berridge, in his car with his driver. He was immediately followed with the usual escort of two armed men with double-barreled carbines. James Hack Tuke, a Quaker and philanthropist, visited Oughterard and its workhouse in April 1880. He said that Mr. Berridge was the largest landowner in the district. He was non-resident and, as far as he heard, does nothing for his tenants. The previous day, he had travelled through a large part of his neglected estate in the Oughterard Union district. William E. Forster, Chief Secretary for Ireland (1880-82), was critical of Berridge as a landlord. He wrote in January 1882 that he had hoped that a reduction in rents would take place on the Berridge estate in Galway but the tenants had got a cruel bargain from their landlord. He said that Berridge seemed to be the worst type of rack-renting landlord, as tenants were generally poor and unable to pay the rents. This opinion came from a man who became known as ‘Buckshot Forster’, as he substituted the use of buckshot instead of bullets for the Royal Irish Constabulary. Alexander Innes Shand, an English traveler, visited Connemara in 1884. He wrote that Mr. Berridge had done little to his vast estate since he bought it and would be very willing to resell it. He had refurbished Ballinahinch Castle handsomely but had never occupied it since the land troubles began. At that time, only a gamekeeper resided in the hospitable house of the Martins. Archer E. Martin, a descendant of the Martins of Ballinahinch, most of whom had emigrated to Canada, wrote from Winnipeg in 1890 that the Berridge family were still in possession of the Martin estate. He said, “it was almost wholly uncared for, neglected and cursed for nearly forty years by the iniquitous rule of an absentee.”

Evidence of Mr. Henry Robinson to the Cowper Land Commission (5th November, 1886)

Henry Robinson, agent of Mr. Berridge, gave evidence to this land commission in November, 1886. His evidence must be taken purely from the viewpoint of a land agent. He said rents were very fairly paid till then, when the tenants were inclined to stop paying rents, as they expected to get reductions in rents. They had asked for a reduction of rents but he had not offered them any as he said the rents were fixed by law under the Land Act (1881).The tenants were able to pay the rents when there was a demand for their small cattle at the fairs and he said the prices were sufficient in 1886, as he had attended the fairs. The rent was paid from the sale of their cattle; the potatoes were only for their own use.

The holdings were very small, the greater part was bogland. About six acres was the average of arable land of each tenant.

There had been many evictions but the tenants went back again after being evicted. County Galway and Connemara in former times had been very quiet and peaceable but there was now agitation and disturbance and it was difficult to deal with the tenants. His father had been under protection, ordered by the government. He was based in Ballinahinch but was land agent for the whole area from Galway along the line to Oughterard and into Connemara. He had just been appointed agent in the Aran Islands, where the average rent was £6 a year. Rev. Thomas Flannery, p.p. of Carna and Recess, gave evidence to the same land commission in 1886. He said the average rent in the area was £5 to £10 per annum. There was a large class of graziers who had 200-300 acres and who paid £40 per annum in rent. On Mr. Berridge’s estate, there had been no reduction of rent as he refused it to the tenants, which pressed very heavily on them. Thomas Conroy, of Rosmuck in the Oughterard Union, also gave evidence to the commission. He said he had never seen the country in such a deplorable state of distress. The tenants were heavily in debt to both the landlords and shopkeepers. Mr. Robinson, the agent of Mr. Berridge, evicted 404 persons in the district a short time ago.

Evictions near Oughterard: Death of an Old Man

In 1875, George Robinson, agent of Mr. Berridge, brought an eviction order against the tenants whose leases had expired, near Oughterard and Kilannin. He said he intended not to remove them, but to rearrange their holdings. The tenants were asked to sign caretaker’s agreements but Fr. Coyne, the parish priest, had told them not to sign such agreements. Caretaker’s agreements were temporary and did not give them the right to be readmitted to their houses and land. As they refused to sign, the Sheriff and his agent removed the tenants, although their furniture was left in their houses. When the Sheriff left, some of the tenants broke into their houses again. Mr. Robinson, the agent, then removed them a second time. Mr. George Robinson, the agent, was accompanied by the Sheriff and Mr. Jackson, J.P. (Justice of the Peace). When they went to the house of John Sullivan of Garrynaghry, Kilannin, he refused to sign any caretaker’s agreement and left his house of his own accord. They then went to the other houses who refused to sign any agreement on the instructions of Fr. Coyne. The agent then took possession of the houses. A few hours later, they were told that John Sullivan, who appeared to be in good health although an old man of eighty-five years of age, had suddenly taken ill and died, shortly after being evicted. When they returned to Garrynaghry, they found the priest, and a mob of a few thousand men and women had gathered. Fr. Coyne told Mr. Robinson and the Sheriff that the old man had been murdered and that he would swear information before a magistrate against them. A coroner’s jury held an inquest the following day and stated that the old man had died as a result of rough handling in being put out of his house. They brought a verdict of manslaughter against Berridge’s bailiff, Bartley Murphy. The coroner ignored the verdict as improper, as the dead man was aged eighty-five and had received no ill treatment from Mr. Murphy or the Sheriff. Some jurymen related that the agent, Mr. Robinson, played on the feelings of the dead man’s son. One account states that the agent, Mr. Robinson, then turned on the priest, Fr. Coyne, who gave his consent to signing Caretaker’s agreements and the tenants were readmitted to their houses and lands. Whether Mr. Robinson intended to evict the tenants, or rearrange their holdings when their leases had expired, it was a bad incident as an old man had died during the eviction.

Richard Berridge Junior (1870-1941)

Berridge’s son, also called Richard, inherited the estate at the age of seventeen. He appears to have been a better landlord than his father, who showed little interest in the estate and was an absentee for the most part. Richard was born on 21st April, 1870, educated at Oxford and lived permanently at Ballinahinch Castle and later at Screebe Lodge, Maam Cross. He was a J.P. (Justice of the Peace), and High Sheriff of Galway in 1894. He served as a lieutenant in World War I and died in 1941. His son, Colonel Robert Lesley Berridge, born in 1927, resided at Screebe Lodge, Maam Cross, Co. Galway. Richard Junior lived in better times than his father, who owned the estate during the height of the Land War agitation. From the 1890s, the tenants were buying out their land and becoming owners under the land purchase Acts (1881-1903). He did extensive planting, especially around Ballinahinch Castle, which gave employment and improved the district. The Berridges favoured the Galway to Clifden railway, which opened in 1895 and ran for twenty miles through their estate. This project had been opposed by the Law Life Society, who owned the estate before them. In 1906, Berridge held Claremount and the tolls and customs of Clareville fair in Oughterard. By then, most of the townlands owned by him were sold, and bought by other local landlords in Oughterard, i.e. Henry Hodgson and John Doig.

The Galway Express reported on 25th September, 1909, that some very satisfactory and substantial reductions had been made in rents for the tenants of the Berridge estate, as a result of a Land Commission Court held in Oughterard.The bulk of the Berridge estate was taken over by the Congested Districts Board on 31st March, 1915 and sold to the tenants. The Berridges retained Ballinahinch Castle and a Demense of 800 acres until 1924. In 1925, the Castle and Demense were sold to Ranji, an Indian cricketer and son of an Indian prince. The Berridges took up residence in Screebe, Maam Cross.

Good and Bad Landlords

Not that all the landlords were bad and unjustly evicted tenants. It is sometimes difficult to quantify the numbers of good or bad.Many of the new landlords who bought out estates that had become bankrupt during the Famine pursued a policy of consolidation of farms and evicted tenants. Numbers of them had a business approach and wanted to make a profit from the new estates they bought. The chief offenders as regards evictions were the Kirwans, Carraroe; Thomas Eyre, Galway; Patrick Blake, Tully, Spiddal; Lord Campbell, Moycullen; C. St. George, Kilcolgan and Oughterard; and the Law Life Assurance Company of London.

The Law Life Company and Richard Berridge were absentees and owned the largest single estate in Ireland or Britain.

- St. George of Oughterard was regarded as an improving landlord, who put money into his estate and employed tenants, yet he evicted tenants during the Famine. There were also good landlords in Connemara during and after the Famine, i.e. Anthony O’Flaherty, Knockbane, Moycullen; Henry Hodgson, Oughterard and Merlin Park, Galway; Mitchell Henry, Kylemore Castle; J. C. Lyons, Clifden etc. These improved the land by reclamation, provided employment and built cabins for their tenants. Rev. S. G. Osborne traveled from Galway to Oughterard in 1849. He wrote that he came upon an estate which formed an exception to almost any he had seen. It was that of Mr. A. O’Flaherty of Knockbane, MP for Galway. Not only all the lands round about it appear well and clearly cultivated. There was unmistakable evidence of painstaking management. The cabins were all in roof and repair; the little holdings well stocked and the people united in the same endeavour. Mr. A. O’Flaherty was the only landlord in the vicinity of Oughterard who believed in tenant right.

Folklore

The Schools Folklore Collection (1937-38) gave many accounts of the local landlords.

The Landlords

A man was evicted in Garrynaghry and the snow was thick on the ground. The poor man died of the cold.

– Mary McDonagh, Collinamuck School, Rosscahill. January, 1938.

The landlords in this place long ago were the Martins and Berridge. The Martins were landlords of all this place as far back as Cashel long ago.They sold the land to Berridge and he was the landlord for a long time. Berridge was not too hard on the people but the Martins were hard enough on them. Berridge evicted Michael O’Connor from his land back in Glan but he let him in again. The landlords gave work to some of the people but the people had to do everything the landlords told them to do.

– Una Walsh, Magherabeg. Kilannin National School.

The Landlords

Capt. Martin lived in Ballinahinch. He could walk through his own estate from Ballinahinch to Galway. He sold some of his estate to Berridge. Many of the townlands around here belonged to Berridge. The landlords were of English stock.

– Killola National School, Rosscahill

The landlords of this district were Berridge, Henry Robinson, Thomas Kern and the Martins. They were about forty years in this place. The rent people gave them were cattle and some of the produce of the earth. They came from England. Berridge lived out at Screebe and the other three in Kilannin, near Oughterard. Berridge was a hard, grasping man in regard to rent and when he died, not many of his tenants in the place grieved over his death. When Berridge died, Henry Robinson became the landlord of the district after him. Robinson was a hard man and he evicted many poor tenants from their farms. The landlords had strong control over the tenants.

– Rosmuck National School, Barony of Moycullen

The Landlord

Almost sixty years ago, the landlords evicted people from their houses. The Martins of Ross were the landlords of Porridgetown. Everyone in Porridgetown was evicted from their house, except Martin D’Arcy, who was taking care of the land for the landlords. They were out on the side of the road in little houses. Some of them were out a few months and others a year or so. The parish priest put them back into their houses again. His house was called Land League House, as it was made at the time of the Land League. The parish priest made it and sometimes he read Mass there. The bailiffs used come every six months, trying to get the rent from the people.

Peter Walsh told it.

– Mary Walsh, Porridgetown

The Landlords

The Martins were the landlords long ago. They ruled Rosscahill, parish of Kilannin and many other townlands. Jack O’Flaherty was the landlord of Oughterard, Glan, Magherabeg and the places around. The landlords used give the people time to pay the rent and thus the people had not a bitter hatred of them long ago. Sometimes they evicted people from the possession of their land and they went to the workhouse or the side of the road. The Flahertys had the land before the Martins and the Martins bought the land from them. It was said that the landlords collected the tithes from the people. Most of the Martins were in the British army.

Patrick Lee, 67.5 years old, told it.

– Mary Lee, Eiscir, Rosscahill.

Landlord-Tenant Relations

Condition of tenants, dwellings, farm size, rents etc. in the first half of the 19th century.

Condition of Tenants

The best account of landlord-tenant relations etc. is to be found in the Devon Commission on Irish Land (law and practice) 1843-44, which took place before the Famine. A short meeting of the Commission took place in Oughterard on 10th August, 1844, which dealt with the Martin estate, the largest in the parish. The Poor Inquiry (1835-36) for the parish of Kilcummin, although primarily concerned with the condition of the poorer classes in the parish, gives a good deal of evidence on the condition of the tenants and their relations to the local landlords. The vast majority of the tenants of the parish were smallholders of land, i.e. small farmers, labourers and cottiers who lived in great poverty and at subsistence level before the Famine. In the parish of Oughterard, 85 percent of the people were chiefly engaged in agriculture and 91 percent depended on their own manual labour for a living. The rest were engaged in manufacture, trade and handicrafts. Even in the town of Oughterard, 50 families out of a total of 132 were engaged in agriculture, i.e. 37 percent.

Kilcummin parish, which consisted of 108,791 acres and 142 townlands, was the largest civil parish in Ireland. The greater part of the land of the parish was bog and mountain. Along the south shore of Lough Corrib, on the right-hand side of the road from Galway to Oughterard, a limestone area, there was some good arable land. In this area, the population density per square mile was over 400 persons in 1841.

In general, the occupation of the tenants of the parish was a mixture of crop cultivation (potatoes and grain) and livestock. But the greater part of the land was given over to pasture, i.e. cattle raising, especially in the mountain districts. There were two separate fairs in the parish, i.e. Clareville and the town, each held four times a year. The population of the parish of Kilcummin in 1841 was 10,106 (rural). The town, given for the first time, had 718 inhabitants, i.e. an overall population of 10, 824 for the parish. Like the rest of Ireland, the population had been increasing from the late 18th century, from 8,099 in 1821 to the above mentioned figure of 10,824 in 1841.

Almost all the tenants in the parish were tenants at-will. They depended on the good will of the landlord from year to year and thus had little security of tenure or freedom from eviction. There were very few leases, i.e. a fixed rent for 31 years or a lifetime. Capt. T. H. O’Flahertie told the Poor Inquiry (1835-36) that he had 40 of his own tenants who held under leases at the rate of 10 shillings an acre. When the leases expired, the landlords often evicted the tenants. The landlord had the power to evict or ‘turn out’ the tenant if he failed to pay the rent or was in arrears of rent. His cattle would be driven to the local pound to be sold at auction and he would be served with a notice of eviction. In 1844, Mr. Cromie, agent of T. B. Martin, was building a new pound at Oughterard and the tenants were paying 1 shilling to him for the pound-keeper.

The two witnesses, small tenants John Sullivan and Michael Connor of Thonewee townland, who gave evidence at the Devon Commission in Oughterard in August 1844, held their land in partnership. Their rent was raised from £14-16s to £12-1s per annum and they were served with an eviction notice by Mr. Cromie, land agent of T. B. Martin of Ballinahinch.The lack of security of tenure was one of the serious flaws of the Irish land system. Mr. Henry Inglis, an English travel writer who visited Oughterard in 1834, wrote that there was a custom to allow one half-year’s rent to be constantly in arrears and in this way all tenants were in the power of the landlord. Hely Dutton, in his survey of Co. Galway of 1824, wrote that a large portion of Co. Galway was let to cottier tenants without any lease and they all blamed this uncertain tenure as the principal cause for the non-improvement of their farms and houses. There was no incentive for improvement. Dr. Kirwan p.p., who gave evidence to the Poor Inquiry (1835-36) for the parish of Kilcummin, said that it was useless to advise people to improve their lands. Their common reply was, “if we showed that we were getting better, so much would be immediately added to the rent; the agent would drive his gig up to the door and raise the rent.”

The Poor Inquiry 1835-36

This Inquiry, ten years before the Famine, for the parish of Kilcummin, gave a detailed account of all aspects of the lives of the poorer classes, i.e. small farmers, labourers and cottiers, who were the great majority in the parish.

In general, the Inquiry showed these classes were living on the very margins of subsistence, housed in wretched cabins, poorly clothed, and often going without food. The distress had increased in the previous ten years, although no one had died from destitution in the previous three years known to the witnesses. In 1835, 150 families in the parish were entirely supported by charity. The potato crop constituted the greater part of the food of the peasantry but they also had oatmeal, fish, eggs and buttermilk in their diet. The clothing of the men was a coarse homemade cloth called frieze. Women wore a flannel or cotton dress, i.e. blue and red petticoats. Men wore shoes but women went barefoot. When Henry Inglis visited Oughterard in 1834, he wrote that many were so miserably off that the parish priest was obliged to become security for the price of a little meal to prevent them from starving.

Dwellings